I don’t think you understand, Leonel Do you know how poets are viewed here? We’re seen as bohemians, or romantics, or crazy. He never explained how he came to be at her door, but in their first conversation he spoke of his conviction that poetry could convey across borders the suffering of others and their hope for a better life. Gomez wanted Forché to join him in El Salvador because he believed a war was coming and that the United States had something to do with it. In the forty years since she accepted his invitation, she has become one of the most outspoken poets on human rights issues in Central America and beyond. “Are you going to write poetry about yourself for the rest of your life?” Gomez challenged Forché, before inviting her to travel to his country with him and write about what she would see there. Nothing had prepared her for what followed.

Gomez’s name was vaguely familiar to Forché: a friend, the daughter of expatriated Central American poet Claribel Alegria, had mentioned him the previous summer during conversations about political unrest in El Salvador. In the back of his car were his two young daughters. Then a man from El Salvador called Leonel Gomez knocked at her door.

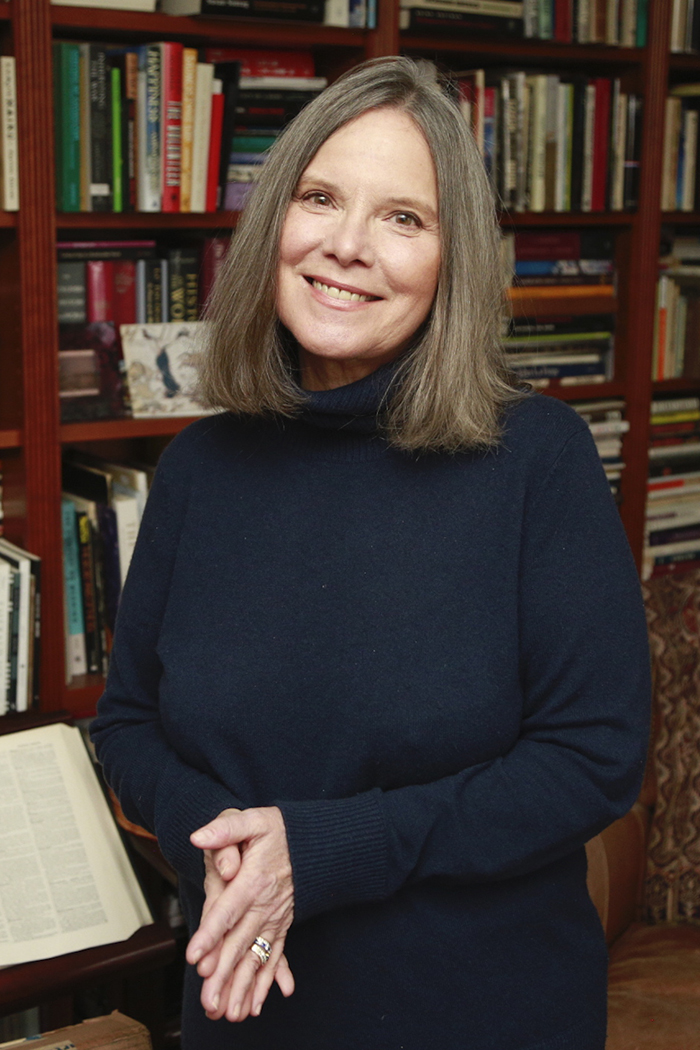

The only consistencies were menial labor and poetry, and, more recently, translating and teaching.” She was already an accomplished poet (her first collection won the Yale Series of Younger Poets competition), but looking back, she sees that in her early work “there was no thread of purpose or commitment.” This story begins in 1977, when Forché was twenty-seven and “too young to have thought very much about the whole of my life, its shape and purpose. What You Have Heard Is True by Carolyn ForchéĬarolyn Forché’s memoir What You Have Heard Is True is the story of her coming to consciousness as a poet and as a human rights activist.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)